Good Pursuit Training Teaches Efficient Driving Response and De-escalation Techniques, Not Just High-Speed Driving

Published

While there is still some debate as to what degree a law officer’s age and inexperience contribute to deadly crashes, it’s broadly accepted that speed kills. Unfortunately, most conventional police pursuit training programs don’t successfully train officers to drive at high speeds in realistic, real life environments such as rural, city or congested areas.

Pursuit Training for Real-World Police Driving

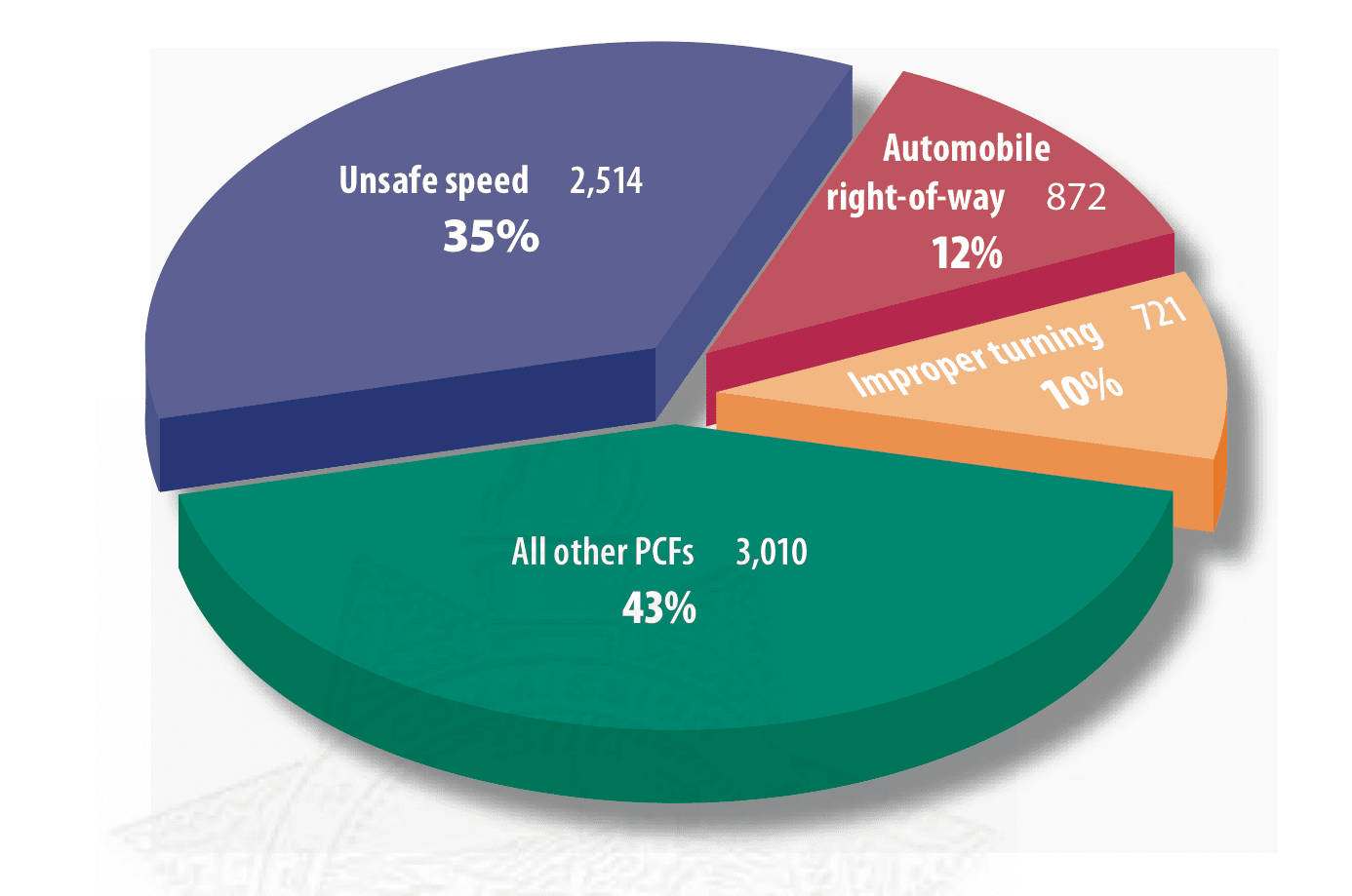

This chart shows the primary causes of all peace-officer involved collisions in California, 1997–2007. (source: Driver Training Study, California’s Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, 2009)

In their 2009 Driver Training Study, California’s Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) noted that, “more than half (55%) of officers killed while driving [in California] were responding to a call for service. … Speed was a factor in the majority of cases (83%).”

In an independent examination of the available nationwide law enforcement crash statistics, Major Travis Yates of the Tulsa (OK) Police Department likewise found speed to be a predominate factor in most fatal and non-fatal crashes. (He ultimately shared his findings in his columns for PoliceOne.com.)

POST further noted that, over a given ten-year period, “7,100 injury collisions occurred [in California] … in which at least one party was a peace officer driver of a law enforcement vehicle.” In those 7,100 accidents, unsafe speed was the primary collision factor 35 percent of the time. When combined with the other two primary collision factors we get a clear picture that the leading cause of police driving injuries and deaths: The combination of fast driving and negotiating intersections. Neither of these skills—high-speed driving and dealing with “interference vehicles”—are sufficiently addressed in most police pursuit training programs.

Single-Vehicle Accidents Prove Deadliest

Both Major Yates and POST found that most fatal police driver accidents only involved the police vehicle. As Yates wrote in PoliceOne.com in 2008, “The most troubling number discovered is the amount of one-vehicle collisions involved in officer deaths. Sixty percent of all deadly collisions involved just the police vehicle.”

Although they drew from a different data set than Yates, POST had the same finding: “Less than half (41%) collided with another motor vehicle.”

Yates concluded: “While many may believe that a secondary vehicle plays a role in officer deaths, the data simply does not indicate that. Of these one-vehicle collisions, the majority of these incidents involved units running off the roadway and striking objects such as trees, buildings and guardrails.”

POST similarly found that a combination of speed and improper turning were likely the case of 45 percent of all police crashes.

Tragically, few of these injuries and deaths occurred during a high-speed pursuit or either emergency situation.

Driving Fast When Not Engaged in Pursuit

According to POST: “it is notable that the [FBI’s] LEOKA [Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted] studies revealed that just 55% of fatal peace officer driver collisions were while responding to a call for service. This indicates that officers are driving fast when it may not be required.”

This desensitization may be the result of overconfidence. As one law officer told researchers Lisa Dorna and Brian Brown: “They build you up, people think they are invincible because of all this building up, you go faster and faster and faster yes I can understand you want to be a confident driver but that’s the problem.” (source) Other researchers (such as Scott E. Wolfe et al.) see it as a symptom of a sort of professional fatalism: “The routine and normality of driving is often viewed as merely part of an officer’s employment, reinforcing the idea that vehicle collisions are inevitably going to occur and are unavoidable.” (source)

In any case, these numbers highlight a major shortfall in current police pursuit driver training courses: The focus sharply on building skills, and thus fail to teach good judgment.

As Yates wrote, “The mental aspect of driving must be emphasized. In many of the driving deaths, a different decision by the officer may have yielded a different outcome. Training should not always be about driving on a track but also in a classroom discussing the thought process of driving. Driving Simulators can have an even bigger impact on helping officers make the correct decisions during stressful situations.”

According to FAAC Subject Matter Specialists Chuck Deakins, “The evidence is clear: Learning how to operate a vehicle at speed is not enough. A complete pursuit training program needs to include proper decision-making and judgment exercises and tests. The best way to accomplish this—realistically and safely—is with simulation training.”