New Academic Research Offers Insight on Improving De-Escalation Skills with MILO Range Simulators

Published

Simulation is an innovative branch of educational technology and a successful medium for teaching critical skills in high-tempo—and oftentimes dangerous—professions. In a variety of settings, simulation education—broadly defined as “a bridge between classroom learning and real-life…experience” by the Society for Simulation in Healthcare—can be used not only for learning core competencies, maintaining skill proficiency, and teaching agency policies but also for rolling out new equipment and processes. It can also be used for developing cognitive skills like creative thinking. In particular, recent simulation training has been focused toward the end goal of productively improving police de-escalation training programs, a research path of one recent CMU Doctor of Educational Technology (D.E.T.) program graduate, Dr. Joy VerPlanck.

In 2016, VerPlanck entered the CMU D.E.T. program and set a course to apply educational theory to force options simulation technology with which she was already familiar, to improve the way military and law enforcement agencies train for crisis mitigation. In particular, her work draws on the theory of cognitive load, a learning theory by Sweller that guides instructional design on the basis that learner problem-solving abilities may be impacted by “selective attention and limited cognitive processing capacity.” When an educational program is intentionally designed with cognitive load theory as a core component, it allows instructors to focus tasks and hone skills without clutter. Moreover, participants experience development by building schemas in their long term memory, enhancing the ability to learn new processes with their working memory.

“In cognitive load theory, the deep cognitive processing to develop useful schemas happens when the trainee is presented with the proper level of prior knowledge, motivation, and instructional support,” explains VerPlanck. “While simulator technology is robust, instructors need guidance in order to use it more effectively with the individual learner in mind.” In particular, she suggests that many police agencies lack the time to use their simulators to focus on learning techniques for crisis mitigation through cognitive development; they merely use it to test reaction times and weapon proficiency. This doesn’t build creative thinking skills or help them manage escalated situations with anything other than speed and accuracy.

VerPlanck’s final dissertation was defended in February of 2020, just before the events of COVID-19 shut down the global economy and the death of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer changed the world. De-escalation training has long been a component of police work, yet the need for more is as great now as ever. “To say that research on de-escalation training is important now implies that it hasn’t always been critical. The reality is, though, we could have been using simulators better since their inception.”

VerPlanck’s final dissertation was defended in February of 2020, just before the events of COVID-19 shut down the global economy and the death of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer changed the world. De-escalation training has long been a component of police work, yet the need for more is as great now as ever. “To say that research on de-escalation training is important now implies that it hasn’t always been critical. The reality is, though, we could have been using simulators better since their inception.”

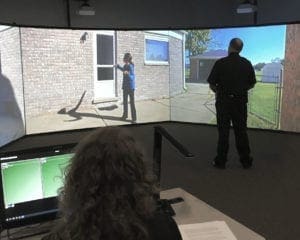

VerPlanck’s study employed mixed methods to explore the potential relationship between simulation training and police officers’ ability to think creatively in managing crises. Principles of instructional design, including aspects of cognitive load theory, were applied in a study of the cognitive load and creative thinking of law enforcement professionals conducting training with a MILO Range use-of-force simulator.

In typical simulation training, officers are expected to decide in an instant if they should shoot or not shoot. In her study, VerPlanck encouraged 51 officers among four agencies to employ a creative or novel approach to de-escalate a situation where they had been called to respond. “When police are called to address an emotionally disturbed person,” VerPlanck explains, “the situation has already escalated. If a citizen was concerned enough to call for help, then the situation is tenuous.” The challenge, according to VerPlanck is that “officers get minimal de-escalation training due to limited resources, so they don’t have opportunities to hone advanced cognitive skills, like creative thinking.”

In this sense, it is not only the use of the simulator as a technology for training that matters; it is also about changing how the simulator is used. This requires a skilled instructor. By providing specific prompts to trainees, ones that encourage and stimulate a creative cognitive process, officers participating in her study were observed being more creative when helping a person in crisis.

For instance, in a simulation where an aggressive person is off their medication, officers might typically insert themselves by asking repeated questions (“what kind of medication are you taking? Do you have any weapons?”). By reducing cognitive load and encouraging creative thinking, officers began to demonstrate behaviors that attempted to bridge connections with the person in crisis. Though these are preliminary results that have been presented in her dissertation, Dr. VerPlanck’s initial research is currently undergoing peer review in industry-leading publications and academic journals.

In 2019, CMU Chief of Police Larry Klaus was the first to enthusiastically get involved in the research. He is eager to learn the results, and how to implement findings into his existing simulator training curriculum. Chief Klaus recognizes that “law enforcement throughout the United States is experiencing transformational change. The change will be multifaceted and officers will be required to perform at a high level of proficiency on every call.”

Klaus has long been a supporter of MILO Range as part of his officer development program, explaining, “the system enables trainers to evaluate officer performance and builds a frame of reference in the decision-making process when an officer encounters a stressful situation in the field.”

Dr. VerPlanck has partnered with Dr. Lois James of Washington State University and with Dr. Troy Hicks of Central Michigan University for her next study in improving officer training methods. Dr. James is an expert in counter bias training and performance optimization for first responders. Dr. Hicks brings experiences and perspectives related to educational technology and instructional design.

The goal of the project will be to look into using intentional instructional design with simulation training to build a more resilient officer. “Resilient officers are compassionate, empathetic, safe, and better equipped to serve their communities,” states VerPlanck. “As we engage in a national dialogue about the role of policing, we must ensure we aren’t simply throwing additional training requirements at them without regard for implementation, A carefully designed curriculum as part of a holistic training program will promote continuous improvement for every officer, regardless of their level of individual experience or expertise, and ensure they are able to respond to crises appropriately.”

Chief Klaus is already on board. “The research and data compiled will assist law enforcement in building better training for our current officers, and for the next generation of officers entering the profession.”